Turning the Tables on the Interviewer

This week we thought we'd turn the tables and put Michael on the hot seat for a short interview. The funny thing is that many of our previous interviewees or their significant others have told us that the interviews unearthed things that they've never said or never heard before and now I know exactly what they mean. Sitting down with my own husband and having a focused talk about where he's been and where he's going with his art elicited a few new things even I hadn't heard before. Funny the things we learn if we just listen. Who knew?

Peggy: Very briefly, where did you grow up

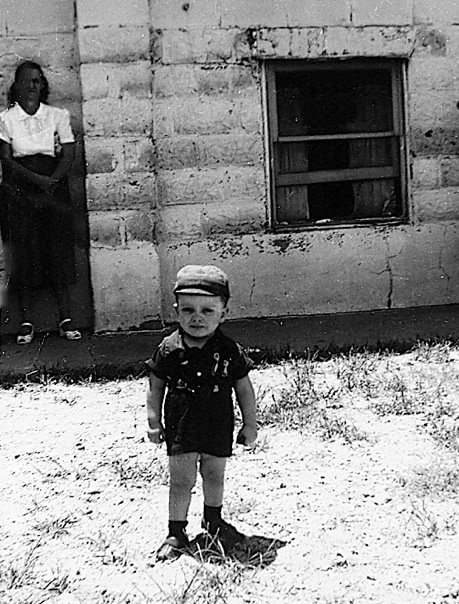

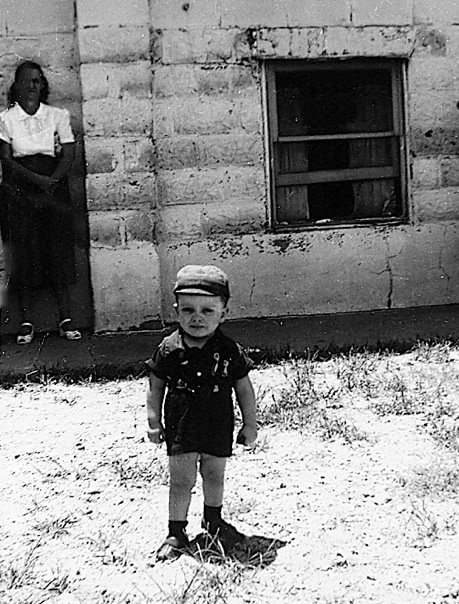

Michael: I grew up all over the Western United States. My mother was kind of a gypsy at heart and my Dad followed her around and the rest of us did too. I was born in Oklahoma and lived in Texas 'til I was six. Then we moved to Washington for a couple of years and to the Bay Area and finally landed in Yuba City where I spent most of my growing up years.

Peggy: When did you first get an inkling that you wanted to do art?

Michael: When I was little I drew a lot. I remember very clearly a Sunday night when I was sitting in church with a bunch of teenage girls who were basically babysitting me and I drew a picture of a cow in a field with flowers and a big udder. I've got that picture but unfortunately I don't know where to find it right now. They just raved about how good I was at drawing. I've always gotten that response from people, so I kind of knew I was good at it.

But high school is really where it came together for me and I had the kind of opportunities and instruction to really discover that I was very good at it. High school is where I became aware that it was my life calling.

Peggy: Of course teenage girls! A little psychoanalysis here, so you got pumped up by the reaction you got from those girls?

Michael: I could be wrong about this, but I think everybody who goes to an art career has gotten rave reviews from people at some formative point in their lifetime about their artistic ability. And that definitely happened for me.

Peggy: So how old were you when you did the cow drawing?

Michael: About five or six. I think it was in Texas, so it would have been not later than age 5. Could have been Washington, but that would have put me at 6 or 7.

Peggy: So you always drew.

Michael: I always drew. I never did anything 3 dimensional 'til junior high and that didn't go very well. I didn't know anything about it. I didn't know any techniques. In my 8th grade art class the teacher handed us a block of balsa wood and we were going to carve it for a sculpture project. I made kind of an African mask. It was okay but it was the only thing until I got into high school.

Peggy: In high school what did you get into?

Michael: I spent about half my time in high school in art classes. Especially, my junior and senior year I was in art classes 4 periods a day. Actually my senior year I injured my ankle and ended up convincing them that I could just sit in an art class for an extra period instead of PE because I was in a cast for 10 weeks the second half of the year. So they just put me in the art class. It meant I didn't walk from my art class to my PE class, I just stayed in my art class which was nice when you're in an ankle cast.

Peggy: After high school what happened?

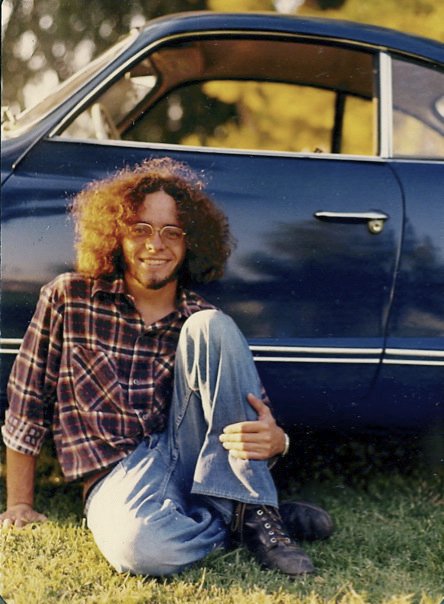

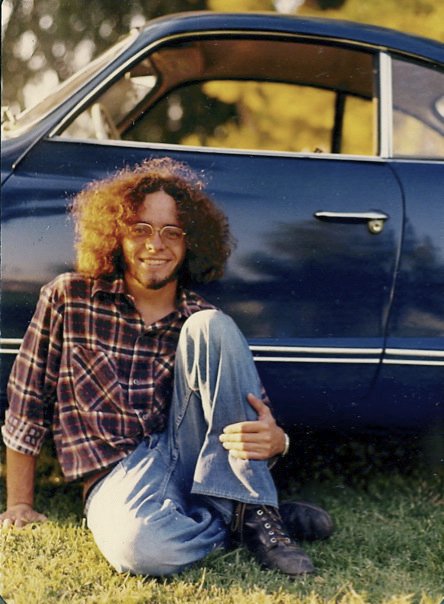

Michael: After high school I bounced around in community college classes knowing I needed to go to college but I had a kind of an anti-establishment hippie attitude that if the man said I had to go to college then I didn't do it. So I didn't seriously go to college for about a decade but I did take art classes from time to time at community college, mostly in Seattle. I graduated from high school in 1970, got married in 1973, and moved to Seattle, but wasn't serious about getting a degree of any kind for quite awhile after we moved. I had this belief that I had missed my opportunity. By the time I was ready to go to school I had this impression that I had waited too long, now I was in the work force and the momentum was all against me going back and finishing a degree because I had a wife and a house and then children. That just made it much harder to go to school. So for years I put off going back to school because "oh well you missed your chance." Then one day I said, "Wait a minute. Every day another day goes by. And every day I could be taking a class and if I take a class now and then whenever I can fit it in, I will eventually have a degree. I don't know when but it doesn't matter." So for years I took classes without every thinking about the goal in mind just knowing I need to take another class and it needs to be focused towards getting a degree.

Peggy: Were they art classes?

Michael: I took classes in everything.I eventually ended up with a degree in theoretical linguistics from the University of Washington. I chose linguistics because it interested me, but the reason I wasn't thinking about an art degree was that it wasn't practical enough. I felt like I needed to have a degree that was more practical. I went from thinking about getting a fine art degree which was impractical to actually getting a linguistics and there are probably a 1000 art jobs for every one linguistics job out there. [much laughter] So in retrospect, I felt like my choice of a linguistics degree was an illustration of a kind of a protection mechanism that I had in place. I was afraid really, I didn't articulate it then, but I was afraid to jump off and take the risk of becoming a full time professional artist. Over the years I think I've realized that I was afraid that I might not succeed and I didn't want to face that possibility, so the easiest way to avoid it was just not to put myself out there. If you don't put yourself out there you won't fail. And it was one of the most paralyzing things that I have had to overcome.

Peggy: And so how did you overcome that?

Michael: You made me. [more laughter] You challenged my excuses and my bullshit stories and kind of helped me to realize I needed to shut up and get busy.

Peggy: So then what did you do?

Michael: Then what did I do? Well. There came a time when you and I moved to San Luis Obispo and we bought Windhook and about this same time you convinced me to quit my job. I had a roughly six figure job, (roughly means barely) that didn't demand a lot of my time or energy, and it seems like it should have been an easy way to have a steady income and get the art done. But in fact the job was very stressful because I had to look busy even though it didn't take more than 20% of my time to do the work. I couldn't really submerge myself in art because I always had to be thinking about whether I looked busy enough at work, even though I was working at home.

Peggy: We've talked about this too, that the technology wasn't where it is now.

Michael: The technology for working from home has gotten better and better. But I think my real issue was I'm of a kind hyperfocused artist. When I'm doing art I'm lost in it and to do that while I'm on the time clock means that something important could go by and I might miss it and get caught not paying attention to my work. So I found that I never really did art because I was too stressed out to go into my hyperfocus mode. So I'd just waste days sitting around thinking about whether there was an email in my inbox or a message on my phone. I couldn't just lose myself in the art, I ended up being very unproductive and frustrated.

Peggy: You took a couple classes in Santa Cruz at Cabrillo before we moved?

Michael: Yes I've taken community college classes in every town I've lived in since high school. I took community college classes in Yuba City—in Marysville next door. I took them in Seattle. I did not take any classes when we lived in Fremont after I came back from Washington. I did take classes in Gilroy and Santa Cruz and then have taken community college classes in SLO. Since I got my degree at UW all of my community college classes have been art related and never focused toward any kinds of credit, I didn't care about the grade. I usually opted not to take a letter grade if it was possible. Usually I dropped the classes before the end of the semester. The semester system is just too slow for me.

Peggy: You said you needed to shut up and get busy, so you took classes and what happened?

Michael: I really started to actively work on an art career after we moved to SLO county. Before that I had just dabbled, persistently, but sporadically from 1970 to 2002 when we bought the Windhook property. Within a couple of years we moved here. And that's when I started to focus. Really when I quit my job I started to pour more energy into how to make artwork.

Peggy: So what did you do to do that?

Michael: At first I was working remotely from SLO, then I quit that. This is all sort of tangled up with our Windhook development. About the time we really started working on building Windhook, I spent a year not doing art but working on building plans and talking to the architects and the County. Then after that, I hired a dozer operator to do the ground work and a foundation guy to pour the foundation for the buildings. I was full-time on construction for at least a year. And once again it was a convenient reason I didn't have to put myself on the line as an artist. I had something I had to get done, so it allowed me not to focus on making art. You're beginning to see a pattern of me hiding behind excuses for things. (Pondering then chuckling)

Peggy: Care to elaborate or continue on that thread?

Michael: As an adult I've always seen myself primarily as an artist. I think I had a more single-minded impression of my own purpose in life than most people I know. I don't know many people who've had as clear an idea of why they're here on the planet as I did. But that self talk of me being this God's gift to the world—I had art teachers in high school, who were not shy about the fact that they thought I was God's gift to the world, and it kind of went to my head. I think I reached the point where I didn't realize that I actually had to work to make it happen. You know, I'm God's gift to the world, what else do I need? [lots of laughter] So eventually after 40 years of that I realized it's not working, something else has to happen.

Peggy: You can't just sit there and draw cows and have teenage girls ooh and ahh.

Michael: Well you can, but it really doesn't get you very far. So anyway, it seems like I've spent my whole life just bouncing from one excuse to another, from one urgent requirement to another and managed not to do much art over that time.

Peggy: So what did you do when you did art?

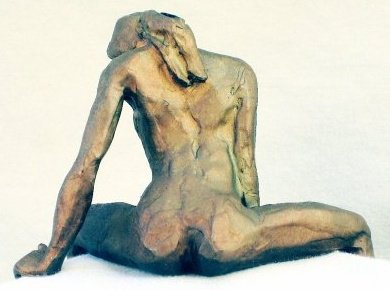

Michael: All of my art is three dimensional. It's almost all figurative work. I just find the human figure to be an inexhaustible source to work from.

Peggy: We'll get back to the form of your art but for the moment, what helps you get out of that pattern?

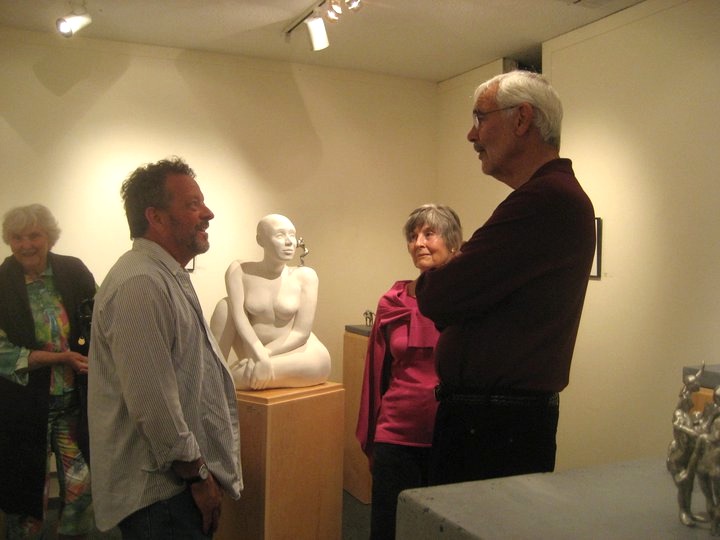

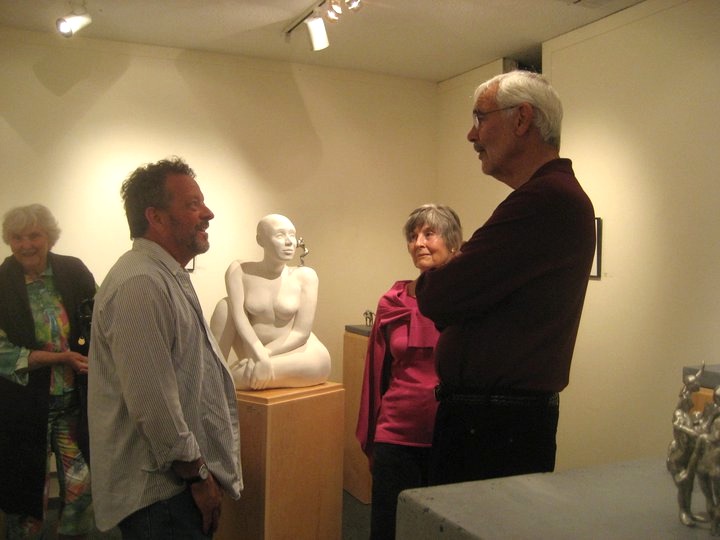

Michael: The only thing that works for me is to put myself in a position where I have to deliver—deadlines basically. Enter an art show and you have to have your work ready to submit on time. Recently I've been very active in the local art community and I've been in a position to create opportunities to show art and take advantage of those in addition to making them available to other people. So for instance the Phantom shows, which we've written about, are a very good example of how I've motivated myself and how I've created kind of a buzz around my own brand. People really get excited about these Phantom shows and they know I'm the guy who's responsible for making them happen. People stop me on the street about when the next Phantom show is going to be. I think the most effective mechanism I have is that. Just making sure there are opportunities that require me to deliver. There's a California Slam show coming up in the Fall and entries are due in May and I have to get ready for that. One of the things we do in these shows is we always make sure the work has to be new work. It means I can't dredge stuff up out of the closet. I have to make something new. Recently I've also put myself in a situation with Studios on the Park in Paso Robles. Studios on the Park recently set up a gallery space. Normally their resident artists pay rent rather than paying commissions. I wasn't in a position to pay the rent. So they set up this perfect studio space in the front right corner of the building, in the window, right as you walk in the front door. There's a handful of sculptors and 3D artists in that space. Studios on the Park normally has attracted a lot of painters but not too many 3D artists, so I basically agreed to put my work in there for a commission. So it's really a gallery for me rather than a working studio venue. And I have to be sure I have enough work available. If they sell something I need to be able to replace it. The other thing about Studios on the Park is they do have work space in the gallery and my plan starting next week is to take some wax tools and wax and various, sort of quiet unobtrusive hand work to the studio and work during their open hours. That's their preferred mode of operation—for the artist to work in the space—and it'll do two things. It'll introduce me to the public in a more tangible way and it will also give me 6 hour blocks where I need to be working. Because otherwise I'm sitting there looking at the walks. I can bring work and kind of show off and chat with the public.

Peggy: You need an audience.

Michael: I do. I actually do need an audience. I'm kind of an extrovert. I've always called myself a closet extrovert. Or a closet exhibitionist.

Peggy: So no excuses, no distractions.

Michael: The psychological issue of my own fear of success is one of the most puzzling things to me. I don't understand why I have it, I don't understand why it's so hard for me to deal with.

Peggy: Those sound like good coping strategies.

Michael: I'm also pretty sure I'm ADD. I've read all the literature on it. The way I got through college was by sitting in the front row of each class that I was in and making a game out of it. My goal was to see how fast I could get the instructor to the place where he was just talking to me and ignoring the rest of the classroom. That was easy to do because most of the class was staring out the window or doodling or with their head down or not looking at him. And teachers are human so they really want someone to pay attention to them. If you sit there in rapt attention and listen to every word they say, pretty soon they're just talking to you. And I found that I really remembered everything that way, and I didn't have to take notes. I'm a slow writer I tend to get bogged down taking notes and lose track and pretty soon I'm so far behind that I can't keep up with the notes. So my strategy has always been to find a way to make the topic fit into my big picture of how the world works. If I can do that I can remember the information. It worked with pretty much any topic. And if I couldn't make it work, I dropped the class because I was in no hurry to finish. I'd wait for another class, another instructor, I think it took me 13 years after I started in earnest to finish my degree.

Peggy: So let's get back to the forms of your work. Why metal?

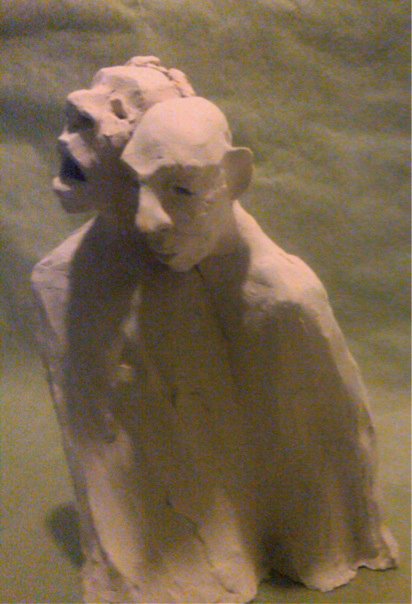

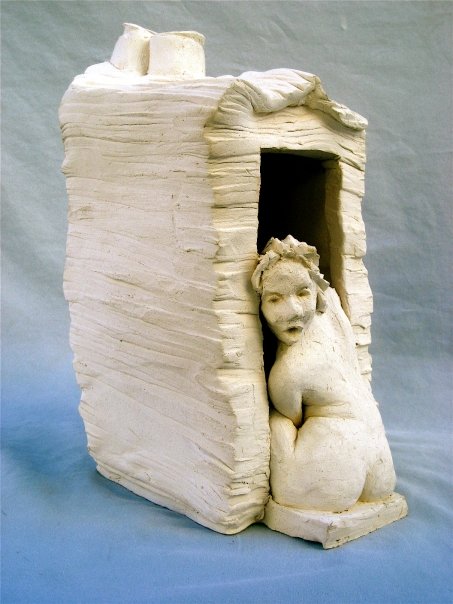

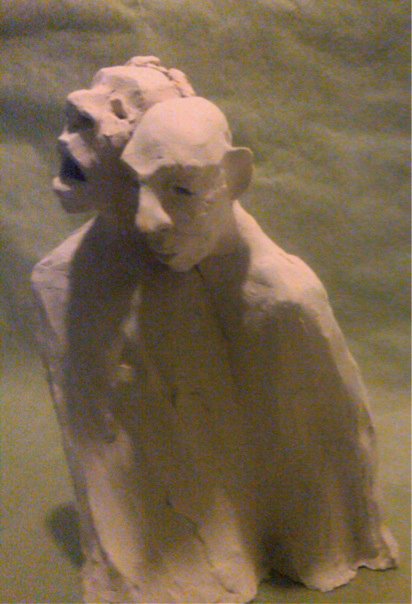

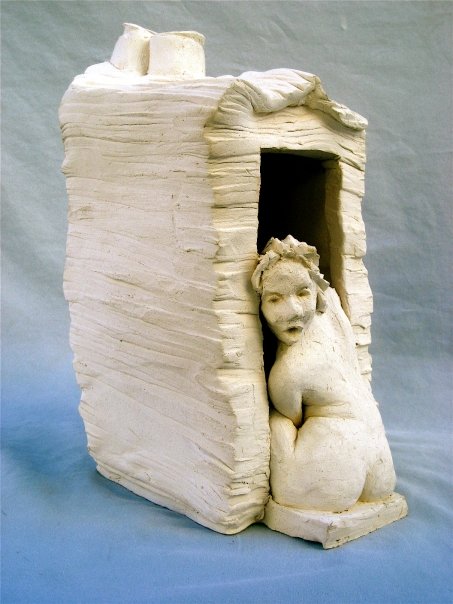

Michael: Because there's fire involved. Almost everything I do involves fire at some point in the process. I did spend 10 years as a weldor in a commercial welding shop making large steel storage tanks. I learned a lot about how steel works. It's a very unique metal in some ways. Before that my primary medium was clay. I did a lot of subtractive work with clay. Most people take clumps of clay and push them together into shapes. I would start with a 50 pound block of clay and I would carve it using clay tools. I would carve the sculpture out of the clay rather than manipulating the clay. I used clay like people carve stone or wood. But clay was very fast and expressive, and I could work as fast as I could visualize. One of the things that impressed my art teachers early was my subtractive approach and theory of it. I was this naive Baptist kid who had never really studied any of this and one time I told my art teacher that my theory of how to do a sculpture is that in this lump of clay there's an infinite number of forms that could be expressed and my job is to isolate one and remove the rest. Take away everything that doesn't express one specific idea or image.

When I told this teacher that, he got this big grin on his face and he said, "Do you know anything about Michelangelo?" I didn't really. I knew he was a big time Italian sculptor from the Renaissance but that's all. So he sent me off to read the Agony and the Ecstasy. He said, "The theory you just described about carving a sculpture was precisely Michelangelo's theory of sculpture." I had never heard that before. I really knew nothing about Michelangelo. The teacher really thought that was cool. It seemed very easy for me to do it. It seemed to me like my ability to create, to express a form, particularly a human figurative form was innate. I didn't learn it. When I started doing it I just knew how. In junior high I struggled to make this mask, and it was crude and awkward and I was not happy with it. But somehow by the time I was a sophomore in high school I knew how to do that, instantly. First time I tried it worked. I don't know if it was maturity or what but somehow I just reached the place where I could do it. I didn't know how. It just worked.

Peggy: You did full on figures, not just heads?

Michael: Yes.

Peggy: And you did figures, and it was metal, the fire.

Michael: Most of my work is in various metals. Recently I've been casting pewter. I've been doing some work with steel. When I work with steel it's still figurative work, it's fully developed figurative work. I don't cut patterns and try to make flat steel look 3 dimensional while still flat. When I work in steel I want the full compound, complex curvatures of the human form and it's hard to explain that. But I don't know very many steel artists who work with steel the way I do. And, Actually it's very difficult so I'm not sure how much I'll do because it's so physically hard. But it's all about the heat and fire and magic. And of course ceramic work involves firing so pretty much everything I do involves heat and open flames. [smiles]

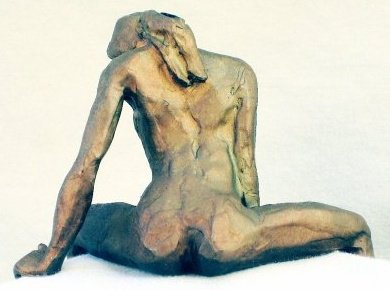

Peggy: What inspires you about the human form?

Michael: Like I said before it's an infinitely variable expressive form and it's also human. I have seen a lot of abstract art that I like but I can't do abstract art. I get bored out of my mind within minutes trying to work on an abstract expression. And by abstract I mean to the degree where there is really nothing representational of the real world in it. For me art is an expression of humanity and I guess I'm just not sophisticated enough to express humanity in ways that don't involve human form. I'm very interested in human gesture and expression. My main thing is just to the gesture as alive and vibrant and dynamic as possible. The other thing about my art is that it's generally got a narrative quality to it. There's always a story in the work I do and what I try to do is capture a freeze frame moment in that story and not give the backstory, not give the conclusion, but just capture that frozen moment in middle of the story. It's an invitation for the viewer to fill in the back story and take it to a conclusion. So the viewer gets to tell me what the story is about. I just give you a scene. It's like those caption contests with cartoons. That's really what I'm doing. I'm doing caption contests for viewers of the art.

Peggy: So what are some of the things you haven't done with your art that you'd like to do?

Michael: I'm actually thinking about some ideas that involve non fire-based media. I recently bought a styrofoam hot knife with some nice features on it and I'm planning to build some large scale styrofoam forms that I can then apply some hard coating onto to make them durable. Essentially the styrofoam would act as a full figure armature and then apply something like Magic Sculpt to the surface. Or it could be carbon fiber applied or fiberglass applied over this styrofoam. The styrofoam would create the basic expression and then you apply the finish surface to it that can handle the elements and the stresses of being in the world. Styrofoam is not good at that. But it's a lightweight strong medium that you can do a lot with.

I've also been playing with Magic Sculpt, which is an epoxy resin clay. Still working in figurative forms, the Magic Sculpt that I've been doing recently has been small figures, sometimes integrated with a contextual element in steel like a ladder or a tower or something. The idea with working in foam is to go large, potentially very large. I'm also interested in working in concrete. I'd like to do some monumental outdoor pieces in concrete.

One of the challenges I have is storage. You either have to sell everything you make or you have to find a place to put it. And gallery space is good storage that gives you exposure out of your studio and exposure to potentially buyers. But anything that's not in a gallery or sold you have to find a place to keep it. And one of the attractions to me in working on the large scale is that we've got 58 acres to store it on and some of it is actually on the road so some of it could actually be seen by the drive-by public. I'd like to see Windhook become kind of a sculpture garden anyway so that makes a lot of sense I think.

Peggy: Have you thought of what could go along the road?

Michael: We just saw an image the other day of a series of bronze bulls in a field. Chris Winfield at Winfield Gallery sent a note out about that. They're larger than life-size bronze bulls that are sitting in a field. I wouldn't reproduce that but we live in cattle country and some kind of cow art would be very interesting. I'm also interested in doing human figures standing out in nature and I sort of have this dragon in the back of my mind that I'd like to do, maybe a 30 foot long dragon that sprawls across the hill, perched by the road and watching the cars go by or something like that.

Peggy: It makes me think of the partially submerged dragon thing where you see parts of the ridge of the dragon's back coming out of the ground.

We could do the concrete together.

Michael: We could.

Peggy: What about water features.

Michael: I'm very interested in water features. I'd really like to work with landscape architects and landscape designers to develop commission works for specific gardens. I haven't really broken into that yet but it's something I'd like to do. And I think the same could be said for architects related to interiors and sculpture related to buildings. I know a guy in Visalia who builds pools. We talked about doing sculptural features integrated with swimming pools, but that never panned out.

Peggy: We've talked about one of the issues with sculpture being that people don't know what to do with it.

Michael: They don't know what to do with it. Don't know where to put it. Don't know how to integrate it into their lives. That's a big issue. People know what to do with a 3 by 5 foot painting—it goes behind your couch on a wall. And that's mostly what people do. They find something that fits on a wall in their house. When they start thinking about 3 dimensional objects they think, does it sit on the dresser, on the coffee table, where do I put it. Where does it go? Most people don't have much of a framework to start with on that so they don't go there. They buy the thing that goes behind the couch or goes above the toilet in the bathroom.

Peggy: Some of your stuff could hit them on the head.

Michael: So outdoors is good space for 3 dimensional art. In fact it belongs outdoors. Outdoors is a place where paintings don't work very well. There are a few specific types of paintings that could work outdoors, mosaics could work. Outdoors is really the purview of the 3 dimensional artist. But indoor space is really good too. There's a lot of 3-D art that really belongs indoors and does well indoors. Like I said people just don't know how to fit that into their interior home space.

Peggy: How do you overcome that?

Michael: I think you have to give them examples and ideas. One of the pieces I'm working on right now for Studios on the Park is — imagine a pass-through window space between a kitchen and a dining room. Not all houses have this, but when you have a pass-through window you can commission it to fit specifically in that space. If you have a 3' wide x 4' tall window between your kitchen and dining room you could put a 3' x 2' grid of flat steel in the top half of that space, and then still be able pass things through in the two feet or so below the artwork but on that metal grid that you've created to fill the space, you put all these figures interacting in some narrative. And so it's an open thing people can see through it, they can talk through it. It creates a visual interaction in that window space. And I'm planning to put one of those in Studios on the Park and hopefully I can inspire people who have a window like that inside of their house with the idea they can put an artwork like that in it.

Peggy: Or inspire architects to design it into a space for a client.

Michael: That would be great if I could get some architects to know what's possible that way. Then they could actually commission it into a job.

Peggy: I know a few architects

Michael: The big challenge is people don't know what's possible and they've never really been exposed to it for how to use 3-D art in a living space or in a yard.

Peggy: You really need a portfolio or images to demonstrate how it can work so people get the idea. Our office doesn't do so much residential landscape but that's where you need the Jeffrey Gordon Smiths.

Michael: The scale of my work in the last few years has been tiny, and that's partly a response to the market. I do these small figurative tableaus involving various figures and various poses and they interact with each other. In the pewter series I've got 22 different figures that I can cast over and over again from the molds and each time I cast a new set of these figures I arrange them into different scenarios and the expressions of the figures are the same but they tell different stories depending on how they interact with each other. An example of that is I've got this one female figure who has her hands cupped over her mouth and she's got her knees bent in an energetic pose. In one context she's whispering and in another context she's shouting, but it's the context that determines that rather than the pose. Those are small because I really had to figure out how to make a lot work without tying up a lot of money. Bronze work is extremely expensive to produce especially if you don't have your own foundry set up. So in order not to have to tackle that challenge I had to develop this whole process for the pewter that I could manage myself much more economically. And I'm getting a reputation for these little figures so I feel like I kind of need to play that out for awhile before I move to the large scale stuff in earnest. I might do the large scale work at the same time but I still want to do this small scale work for awhile longer.

Peggy: So what keeps you going?

Michael: There just isn't really anything else. That's all there is. It's all I've ever seen myself doing. I've seen myself as being on the planet to make art since I was 16 years old, even though I haven't done very much of it. So for me the challenge is to exorcise the demons, the fear of failure, which is an odd thing because I'm never had a negative reaction to what I've done. There's no evidence that the work is going to be rejected so why am I afraid of it? There is an aspect of this whole equation that we haven't talked about which is sales. I get huge support and enthusiasm about my art verbally, but I can't really say that it's mapped out to a financial commitment. People pay lip service to how good it is or how much they like it but only occasionally does some one buy it. Then no matter how much people talk about it if somebody isn't buying it that sometimes undermines my sense of security about it.

So recently you asked me a question about this that I hadn't really thought of before: "So what if you just make it your gift to humanity and don't worry about if it sells or not?" and so I said to myself, ok so that's very true and that's the way I should approach it. Then if it sells it sells but if it doesn't sell I've still got to do it. I think it's toxic for artists to worry about whether or not they're going to be accepted as artists. I think it's one of the most toxic things to listen to. And that's first hand experience. It's the artist's job to make art. It's somebody else's job to evaluate that art.

Peggy: Is this something you've ever talked to your art buddies about?

Michael: Recently I had a conversation with Mike Hannon and Robert Oblon. It felt like an intervention. They sat me down in a coffeeshop and they ganged up on me and they told me, "Look dude you've got to just step up and do it, quit making excuses." You know excuses can be very subtle. We write a newsletter every week. I write 2-3 weeks every month and when I'm not writing I'm doing the coding work and the preparation work to get the email and the newsletter out on time. it takes a lot of my time. And there may be a level at which this is one of those distractions that I can focus on instead of spending time in the studio. The whole Windhook construction project really functioned as a distraction to keep me out of the studio. These are all good things but they still keep me out of the studio. And what I found is that some of the most diabolical distractions that interfere with your ability to just do the work are very good things. Very noble, very inspired, very beautiful, very wonderful things to do, yet they're not the thing you're here to do. There's a real challenge in being able to do the things that are expected and required of you in life without allowing them to mess with your studio time. It takes a lot of discipline.

Peggy: Now for our classic wrap up question, what would you tell someone starting out on their creative path?

Michael: If you're young and you're just beginning to get the kind of inspired encouragement that triggers a move towards a creative lifestyle, don't listen to the practical people—the well meaning friends and relatives who can't see how you're going to survive. They mean well but they are dangerous. If you have a sense of this calling—and if you don't have a sense of calling for art then you probably won't have the energy to follow through, but if you do have that calling, find the people that can help you and don't give up. If you're later in life and you've been resisting that calling, or you've just discovered it, I guess the story is the same. Don't give up and don't listen to all the reasons you can't, because I'll guarantee you you'll find plenty of reasons you can't. And for both groups of people I would say, follow your inspiration rather than your logic. Logic is going to tell you all the reasons you can't do it and it'll be a compelling case because our society does not support art, our society does not make this an easy path in any way. You have to get your vision clear. If you're in turmoil over this then resolve the turmoil. Do the work. Do the work on yourself to get clear on why you're doing it and then go for broke.

Peggy: You should listen to yourself [laughing]

Michael: Yes I know. I think one thing that helps with this is to be open about it. I'm talking to everyone about this now. I'm spilling my guts about the obstacles and challenges. I've opened up so I can't hide behind it.

If you're private about this it's easier to hide from it.

|